Dog

Gathering Ground: A Reader Celebrating Cave Canem’s First Decade Edited by Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady. Camille T. Dungy, Assistant Editor. Introduction by Elizabeth Alexander, Harryette Mullen, and the Editors. (

University of Michigan Press, 2006)

Explanatory

Preface material:

Cave Canem is a nonprofit organization for African American poets founded in 1996 by Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady. Each summer fifty-two poets (about seventeen new poets a year, with the remainder returning for their second or third summers) take part in a one-week workshop / retreat. Over the past ten year over two hundred poets have gone through Cave Canem’s summer program. Since they return to the workshop / retreat for three years during a five-year period, Cave Canem poets have built a network of connections and support that lasts well beyond the workshop week in June.

Meaning, presumably, that a poet who returned for three years would meet eighty and somebody-odd poets. The contributors here number roughly one hundred and twenty or so—more than half of the participants.

Contributors: M. Eliza Hamilton Abegunde, Opal Palmer Adisa, Elizabeth Alexander, Lauren K. Alleyne, Holly Bass, Venise N. Battle, Herman Beavers, Michelle Courtney Berry, Tara Betts, Angela A. Bickham, Remica L. Bingham, Shane Book, Angela Brooks, Derrick Weston Brown, Jericho Brown, Toni Brown, Gloria Burgess, C. M. Burroughs, Lucille Clifton, Taiyon Coleman, Lauri Conner, Curtis L. Crisler, Teri Ellen Cross, Traci Dant, Kyle G. Dargan, Hayes Davis, Jarita Davis, Kwame Dawes, Jarvis Q. DeBerry, Toi Derricotte, Joel Dias-Porter, La Tasha N. Nevada Diggs, R. Erica Doyle, Camille T. Dungy, Cornelius Eady, Michele Elliott, Phebus Etienne, Chanda Feldman, Nikky Finney, Reginald L. Flood, Cherryl Floyd-Miller, Krista Franklin, John Frazier, Deidre R. Gantt, Ross Gay, Regie O’Hare Gibson, Carmen R. Gillespie, Aracelis Girmay, Monica A. Hand, Michael S. Harper, Duriel E. Harris, francine j. harris, Reginald Harris, Yona Harvey, Terrance Hayes, Tonya Cherie Hegamin, Sean Hill, Andre O. Hoilette, Lita Hooper, Erica Hunt, Kate Hymes, Linda Susan Jackson, Major Jackson, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Tyehimba Jess, Amaud Jamaul Johnson, Brandon D. Johnson, Karma Mayet Johnson, A. Van Jordan, Carolyn C. Joyner, John Keene, M. Nzadi Keita, Ruth Ellen Kocher, Yusef Komunyakaa, Jacqueline Jones LaMon, Quraysh Ali Lansana, Carmelo Larose, Virginia K. Lee, Raina J. León, Doughtry “Doc” Long, Kenyetta Lovings, Adrian Matejka, Shara McCallum, Carrie Allen McCray, Ernesto Mercer, Dante Micheaux, Jonathan Moody, Kamilah Aisha Moon, Indigo Moor, Lenard D. Moore, Harryette Mullen, Marilyn Nelson, Mendi Lewis Obadike, Gregory Pardlo, Carlo Toli Paul, Gwen Triay Samuels, Sonia Sanchez, Tim Seibles, Elaine Shelly, Cherene Sherrard, Kevin Simmonds, Patricia Smith, Tracy K. Smith, Christina Springer, Christopher Stackhouse, Nicole Terez, Amber Flora Thomas, Samantha Thornhill, Venus Thrash, Natasha Trethewey, Lyrae Van Clief-Stefanon, Wendy S. Walters, Nagueyalti Warren, Afaa Michael Weaver, Arisa White, Simone White, Carolyn Beard Whitlow, Karen Williams, Treasure Williams, Bridgette A. Wimberly, Yolanda Wisher, Toni Wynn, Al Young, and Kevin Young.

One approach: a sampling. Not a cento—no dismally mechanistic dispersal of others’ work into some whiteboy notion of “multivocality”—that tenor gets voiced without my assistance. (Every African-American in the country grows up learning—at

least—two distinct languages, is what I wager.) A few lines out of each piece, grabbed without prejudice, that is, no fore-notion or slant towards the “typical” or the “atypical” either. The selections follow the alphabetical list of contributors (above). (There is something like a crazy democracy at work in assigning

each writer one poem: guarantee that

nobody’ll be adequately represented. A riff offering a few lines out of each and every poem is, I suppose, a logical, if plod-prone, extension of that. Snapshot of a snapshot.)

My own mother passed this gift to me: the ability to simultaneously

lose my country, my self, my secure knowledge that I

owned the world.

—

i would do it again

work my way

through the hatred

—

In the early nineteen-eighties, the black men

were divine, spoke French, had read everything

—

skin like blood like wine like war binding tight the white flesh, the black pits

pressed into the narrow center sleeping like sin like sex

—

a blueblack star marked my birth

a razor blade cut my course

a razor blade cut my course

—

I ain’t got to whine to let him know his place.

I’d be starving if I ate all the lies they fed.

—

I remember like it was last Tuesday:

our mutual parting of the ways come

on account of a can of 10W40

—

elbow-high gloves gargantuan on the slender arms,

head tilted like a sunflower, legs spread,

and the sharp sucking against the teeth—

—

The landlord told Raymond’s mother that twelve dollars

would be deducted from their rent for every rat killed.

—

In the wake of my fifth bite

of pear, two women, a visiting cousin

and Marse’s new wife, were killed.

—

On Wednesday—pot roast and hotwater cornbread,

the cornmeal sifted as fine as loose road dust

lifting to settle on trousers and lace socks.

—

we’d say Wow to the crushed-can collector,

yeah, that funked-out guy we down with—

he one street off from cool now

—

On Saturdays twicedamonth after a breakfast of pancakes and sahshees we went to visit the sick and shut-in or the well and shut-out (of a right mind).

—

Time is your

hard breath

in the field.

—

Grandmother breaks to wring and squeeze the purification towel free of water, soap, and a bricklike, muddy dirt. Child, all that noise ain’t necessary. If you could see this nastiness, you’d be thanking me.

—

we dark still living

who crawled or

were dragged

hair matted flat

—

In angry mists, you see them, round hands

reaching, beckoning their beloveds.

Today, the sun burns through marine-white air

—

She wants sounds pinioned,

melodic as high-voiced

canaries carousing, half-

singing

—

“the trees wave their knotted branches

and . . .” why

is there under that poem always

an other poem?

—

and we fight over your

foolishness thinking love

can come in a redbone

—

and she went to work manufacturing lines of general foods

where she punched time until they forced her to retire

and in giving up work she opened her backyard bar

—

We had lookouts

in the alleys and the tall kids jumped the fence and the runners ran

with the bags. Peaches were easy. In the graveyard we had no trouble

getting peaches from the dead.

—

the pulp of your carved initials

made with the solid grasp

of a still-forming hand

—

My arm, the arm

of all our fishing generations,

who knew land could be sold

from under you.

—

Hell, round them all up—in minutes

we’ll be standing knee deep in

the unselected poems of black literature.

—

Comfort is helping him pee, or lifting him

onto the toilet, waiting, wiping after his bowels

stir reluctantly.

—

Across the ocean and decades

before, two boys called each other

in Crioulo.

—

Gangly man, skin like red dirt,

you have let rip,

a streak of living

across these here United States.

—

Says she’s seen my kind and knows me well:

Seditty. Too stiff to get down.

—

he would load mustard on a saltine, lay a little

fish on top, & tip it with a juicy slice

of onion.

—

If he turns his sax upside-down

it curves like a question mark.

What is a true measure of music?

—

sip of— jet mighty joe young overgrown

deep plum baby daddy DMX

—

crawling back to you naked over porcupines

selling my qualms and other precious possessions

giving you all the proceeds

—

Can’t say as I blame Miss Amy her grip on the house. Heaven knows, her husband’s a first-rate

scoundrel, and a groggy fool to boot, Master Jackson was in amongst the ’taters with that servant

girl name of Lena.

—

A deal with the devil

In blues terms, the tongue we use

When we don’t want nuance

To get in the way

—

The easy way out is, I am nothing.

I have nothing, so I collect things.

—

Blue jays caucused in leaves, vowing to conquer

berry fields as water rehearsed its verses.

—

Over dinner my mother talked stories

of her father stringing hogs

for November slaughter as segue

to discussing black family mobility

—

The idolized air

once loosed

is never free.

—

just one-day’s walk and this sumac and sagebrush church

could be worshipped hard in Latin under the most wild sky

—

in glyph, the mind of percival everett’s baby ralph asks, “is a photograph always present

tense?” as in here I am!

—

the few black boys here circle white girls

who sprout from these backroads, smell

of hairspray and floral alcohol of drugstore perfume

—

at once to be sly and unsly, no so

unlike those terrible dancehall bodies

—

I know the scratch of bark between my legs,

the dogwood’s smooth deception. Their guilt-stained

flowers ushered winter, the smell of death

—

Song like marble spun

into silk. The human

loom.

—

Or teach us the phonics of bulleted speech no

Blueprint would show how to build a new brick

To stitch a new tower from us to the voice all

—

Hand on hip, I stood defiant.

How far could a broomswept

Head go anyway?

—

isn’t there a word

for yellow-husk morning

of coke-eyed soldiers

—

prep. 1. origin or cause: Aaron begets Helen, Laura, Ermine, Christine, Inez, Beulah, and Sonny. Sonny, he died of female complications. 2. material or substance: the house was built of bricks

—

yet Mingus caught Pres’s stride in ballads

easing of the glottals his very song eclipsed

in the high registers down low in Kansas City

—

Now and again a hoopty livery cab would chuckle along, rolling its heavy engine: Goodie-bye, it would say like mythical Ibo flying away

—

They say . . . well, they say nothing about you, Mr. DogEared,

because you disappeared. Side rocking and silly toed,

Vanish man across the sideways bricks of buildings, hesitant.

—

Boxed-in from birth by the Boogie-Down,

“freedom” what could be taken in the streets,

from a bottle or a blunt.

—

I stumble in the memory

of Ohio, old names and faces

given me: Pecola, Dorcas,

Violet, Nel, First Corinthians.

—

I was to be taken somewhere and given a name

More bona fide and afflicted, I was to be shot

—

My name is Lovely

And I’m so

Pretty

My hair is long

And yours is not.

—

red delicious red but red

like redeye gravy on grits

at Gus’s or red like stoplights

—

spills tripe and bowels

like curses, like obeah

into the killing pan

oily, visceral proteins smell the air

—

Thirty years of marriage sits between them

like a bomb.

—

You have to

English

the world to

become its possessor.

—

A flick of her wrist,

flap: “His eyes are on the sparrow

and I know he watches me.”

—

Because she was homesick for the smell

of Virginia tobacco and pit-roasted hog

—

Hannibal grasps a Roman

monkeybar on history’s rung, and the mighty heroes at recess

lay dead in woe on the imagined battlefields of Halo.

—

Yes, these predictable fifths. O, the blues

is all about slinging those low tales out

the back door

—

leadbelly you say.

killer huh

singer huh

—

Long from those indifferent hours,

long from the doors of the Maison du jouir

and the affected gaze of his mistresses.

—

somewhere, lips print a cigarette, low tones chase

smoke from her mouth, crawl into the ear of another man

—

machete is our music, pianissimo the cut. I sing into the dip between

shoulder and spine. elucidate the nape. how the belly infuses the barren palm.

—

You no longer question

What kind of blue pulls a man’s skin

So tightly over the face.

—

I want to leave behind the icy surge,

The cold I felt some twenty year ago

In October, when coral leaves wither and fall

—

and she missed not a note, hunched over that microphone,

song after song sweating through her spangles

like a dockworker, as men slid to and fro in shade

In front of the box stage.

—

whisky in her treble some nights

moan making a slack belt

revival hymn to salt pork fingertips

—

Fathered by a white desire,

vials, by a quarter-T,

a lighter, needle, spoon.

—

mockingbirds arrive with stolen songs

& cries, their unspeakable lies & omens

as if they are some minor god’s

only true instrument & broken way

—

She curses loud in thick

patois, then calls on Jesus, but no one looks away from the corpse

laid out in front of the rose settee.

—

mean got dis suit fo ya john aint nobody worn dese clothes befo

walk proud in dese clothes dese is free mans clothes

—

Then with the severity of knives we drew seven from the bone-yard,

The common pile of thick and heavy permutations of dice.

—

rocks of rejection

were thrown at her because

of the yellow tone of her skin

not high yellow

—

humming a respirator song

“I put slight faith in his own affirmation”

a man is as constant as the devil on holiday

—

devil chasing his wife

down the street with a stick

she trying to run with only one shoe on

—

Reluctant yellow light ties her fawn-colored lips shut. Behind resplendent fresh her teeth are clenched, her jaw is lantern.

—

Nobody, woman

or man, knows how to handle Al Green.

That Girl from Ipanema would have

dug Al.

—

I am the woman at the water’s edge

offering you oranges for the peeling,

knife glistening in the sun.

—

Lionel Hampton

“Flyin’ Home,”

riffin’ on his

vibraphone

—

neither the hustlers nor

the pharmacists peddle the elixir

that banishes the Wolf, the Butcher,

the Posse—

—

& sits on the floor pulling out her hair

one strand at a time,

trying to weave it into the carpet

with a piece of fingernail

—

is on her back cramming

my hand down cropped

denims. Her left leg,

a pine cone pendulum

knocking against the vanity.

—

You figure if you don’t “get” me,

I’ll somehow get you good—

invading and transforming the habitat forever.

—

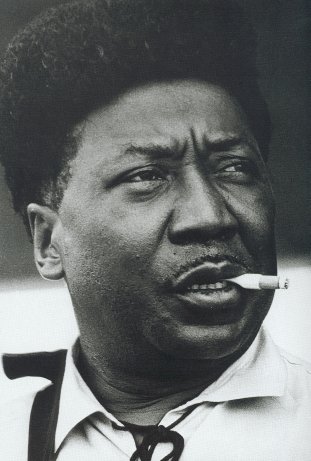

Muddy Waters sprang whole, dry-

heaved from the knotted center

of a plank-wood shack.

Shook hisself loose of blood,

dirt, moonshine, the ass-dark end

of a mule

—

how my father ducked rounds

beneath a sky like heavy blankets

that smothered soldiers in sleep

—

You thirsty? You buy us mojitos? You bring your yanqui dolor. We show our splendid squalor.

—

Or would you think her capable only of lies

because her hands are rough from scrubbing floors?

—

Dear Dear, what is this about? i want to know and don’t want to know.

Do you imagine here is also such a thing as an UNwilling reader?

—

I could see the dark Turnpike for miles, the somber

office buildings winking insomniac cells, the tarmac

spread before us like a picnic blanket and you, like a jade Buddha

—

Had an interesting conversation with a crew member.

He asked me which coast of Africa Haiti sits on.

I told him Haiti is an independent nation on the Atlantic

where you currently preside and showed him your picture.

Uncle, he laughed at the idea of a Negro president.

—

and scatter my ashes

all over Old Town,

once entirely owned by

my Free Mulatto Triay grandfathers

who built the seawall on top of

Seminole bones

—

i bled an owl’ s blood

shredding the grass until i

rocked in a choir of worms.

obscene with hands, I wooed the world

with thumbs

—

I gotta hand it to you though—

all the colors, the smells, tall,

petite, skinny-minnies or whoppin’

whale-sized motha’humphries—you

got variety

—

Should I waltz or shake

my hips in fast huckabuck

Is it minuet or juicy grind

—

For a franc, every stratum can view

the exhibition of the latest hottentot.

One would presume that Robespierre still

reigned over the tricolore, the fever for blood

hot

—

He called Emmett Till a mansion,

a mansion of a boy

whose rooms we

must fill.

—

Now when ’retha’s

fleeing screech reach been-done-wrong bone, all the

Holy Ghost can do is stand at a respectable distance

and applaud.

—

They defy gravity to feel tugged back.

The clatter, the mad slap of landing.

—

I remember him hyperactive lean.

Fragile as grinning watermelon

salt shakers nudged off of antique

store shelves when Black folks shatter

drop history for the sake of propriety.

—

That look, what undermines breath’s pace—

diadem, sloping, reticular hair, pronounced intelligence

how embellished the drunken curve of the moth’s

recursive slanting course

—

we bank our fires and wait.

eventually sleep scratches at the back door,

stubbled with radio static, barbed constellations.

—

I turn the dress loose—its hand-sewn collar,

its seven bodice buttons, the hem’s frayed edge.

I follow each stitch as it slips

from its hold.

—

I fed up wit she jokin me wet paper bag of a city.

Dis dotish Yankee gyul.

See she body drape ova de ledge so?

Watch me fix she.

—

Justice won’t be swift to rescue us

From the clutch of history’s dark lot

—

In 1965 my parents broke two laws of Mississippi;

they went to Ohio to marry, returned to Mississippi.

They crossed the river into Cincinnati, a city whose name

begins with a sound like sin, the sound of the wrong—mis in Mississippi.

—

Come and fry my catfish, baby,

But make sure the grease is hot.

Boy, I got your side meal ready.

Grits are bubblin’ in the pot.

—

Paper reads “Brown Pelicans Shot” along the coast

of Malibu. No one knows if it is a ritual sacrifice,

but birds are not harmless if one loves them

—

would not be moved when called nigger

would not from the lunch counter move

to eat at the Colored hole in the wall out back

—

I can see the white folks’ heads checking

available cash in front of naked Africans

chained, bereaved, and listening to

a cruelty yet to be born. I can smell

the congregation of odors

—

259 Brooklyn Avenue, WARWICK, named after a 14th-century

Military leader, is guarded by a band of black boys, conscripts

Of their own gang, where they’re forced to wear their blood

Reversed.

—

the two halves needing to be joined

back to themselves but only by you

the hum of her throttle but not her berserk

the pleasures in the sound s it makes

just before it buckles

—

Come Monday, I’ll dustmop, repaper with multicolor

Prints, zigzag zebra stripe rooms, fuchsias, no dark

Blue or sober gray, none of the colors that you love.

—

Se wo were fi na wosan kofa a yenki

It is not taboo to go back

And fetch what you forgot.

—

a jimmy choo shoe 99% off poem

a baby let me get that poem

a you don’t look a day over thirty poem

an I can still wear a belly shirt poem

—

Don’t call me rose baby, treat me like daffodil

Need some prunin’ and some trimmin’, I could give you such a thrill.

—

I’ve watch a humble church rock

with a congregation of one, sometimes two,

your bed a sinner woman’s pulpit,

your body an aisle for conniptions.

—

The uncle sat

in a dinghy nearby,

just quiet, the whole four hours

the rescue crew worked.

—

To go for broke, in the gospel sense,

means giving up everything you’ve got (or thought

you had) to God. Give up everything you were (or thought

you were) to the Lord.

—

I tried but God’s

still unlisted.

I don’t mind using

love letters for fire

but at least leave me

some whiskey

to fan it higher.

Whew. Something a little dogged about that “mode,” typing up the material. Conversely, though, there is the way that, under such hard handling, the material exhibits soonest its durability,

or, its friability. Burning hard, or coming apart in one’s hands. (The experience is even more intense in the task of job-stick typesetting for letterpress, a high-recommend to individual writers whose raillery and verbosity is fit to swamp the writing.)

Harryette Mullen remarks (part of a tiny history of Cave Canem wherein she explains how

Cave Canem refers to a sign at the entrance of a poet’s house noted by Derricotte and Eady whilst touring the ruins of Pompeii—a sign meaning “beware the dog”) that “As African American poets traveling in Europe, they were aware that what is called “black experience” is only a part of the life that black people actually experience. They knew that pertinent experience of black individuals and communities often goes unrecognized and unrepresented in literature, art, and popular culture. They envisioned a productive space where black poets, individually and collectively, can inspire and be inspired by others, relieved of any obligation to explain or defend their blackness.” Too, Mullen writes: “What seems to characterize the current conversation is a greater tolerance of difference, uncertainty, and even confusion in our lives and in our work as poets. We can exist as black artists without hermetic definitions of art or blackness.” Something probably apt for all writers: it’s a restless era, one tending less to pronunciamento and certainty.

And I—whiteboy—read the collection how exactly? I see blues and blunts, and a mean sense of history, and the ornery (and ordinary) devastations and redemptions of sex. Or is that just seeing what being a whiteboy in the present historical moment taught me to see—after all, I grew up reading Piri Thomas, and Malcolm X’s

Autobiography, and H. Rap Brown, and Eldridge Cleaver, and Dick Gregory, all that for just that reason: for the nitty-gritty lacking in my own liberal Midwest university town surround. Having found it (and loved it) once, am I “condemned” then to see it (and it only) forevermore? I see little form for form itself—though there are sestinas, rhyming quatrains, a pantoum, blues. I do see still (despite the expressed desire to leave blackness somehow behind), a nearly complete refusal / inability to do so. (Such is the power of

representation’s past—without a determined rupture, it endlessly reproduces itself.)

Cave Canem mosaic, Pompeii