A Tree

The Line, by Jennifer Moxley (

The Post-Apollo Press, 2007)

A little joke it is, calling a book of prose poems

The Line. Though Jennifer Moxley’s referring to something less prosodic: “You will find the line. It extends backwards eternally into the past and forward into the future. The utterance cup, the gentle metric, old words new mind lost time and loves. You sensed it all along, but gaining the knowledge was hopelessly muddled by the inherent drive to author new life. Now cut the spittle line spun into reason and enter the grave alone.”

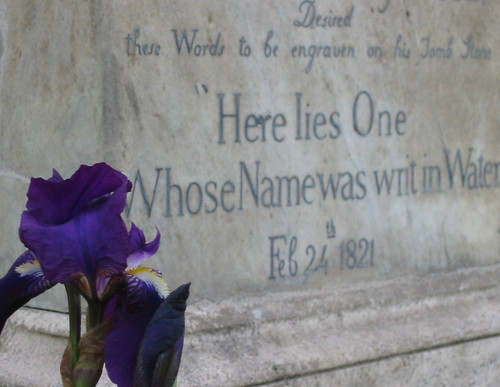

That seems to move precisely out of the “fit” of lineage, out of the inheritances and expectancies of one’s (constant, “muddled”) battle to find one’s place in a writerly line, and into the littler, ordinary (or bigger, “common

and extraordinary”) world of offspring, that grave-denying futile push. It’s a complicated tangle of emotional work, and deftly sketched. The poem ends: “In other words, write. Find time in words. Replace yourself cell by letter, let being be the alphabetic equation, immortality stay the name.”

William Matthews used to talk about the “body of work” and how it inches up to replace the skinnying down body itself. Rather like the way he ends “Pissing Off the Back of the Boat into the Nivernais Canal,” talking about the imagination:

It knows itself

to be tragic and thereby silly.

And it can tell a dull story well,

drop by reluctant drop.

What it can’t do is be a body

nor survive time’s acid work

on the body it enlivens,

I think as I try not to pitch

my wine-dulled body and wary

imagination with it into the inky

canal by the small force

of tugging my zipper up.

How much damage to themselves

the body and imagination

can absorb, I think as I drizzle

to sleep, and how much

the imagination makes

of its body of work

a place to recover itself.

Typing that, I think there’s some vague connect, some implicit mattering between Matthews’s work and Moxley’s. Is it merely a willingness to drop image for idea, make a discursive (field-running, field ruining) poetry of essay and wedge? Matthews, in obeisance to a “period,” is likely to’ve chock’d up the imagery

more, allow’d it its terrible chores, though, finally, I think what he loved

best were ragged little truisms, the ones that nearly annoy, nuisances pearling up, grit in the oyster: “Music’s only secret is silence” or “I knew the way music can fill a room, / even with loneliness, which is of course a kind / of company” or “thus what we lazily call ‘form’ / in poetry, / . . . is Language’s desperate / / attempt to wrench from print / the voluble body it gave away / in order to be read.” (Addenda: Moxley’s work is less glib, less jazz-inflect’d, less ludic, with none of Matthews’s boyish

too-cleverness, that tendency to skirt the edge of smarm.)

Is it possible that I’d read

The Line differently if I hadn’t read the lengthy interview with Moxley (by Daniel Bouchard) in the recent issue of

The Poker? (Frankly, I’d

intended to read it differently—Moxley nowhere mentions Matthews.) What she says, pointing to the series of prose pieces of

The Line, is how “language takes up time. And it’s chronological, so every time you create a narrative, every time you create grammar, syntax, you destroy time.” Expanded, clarify’d, pester’d a little:

. . . if you can imagine the image of a human being disintegrating from top to bottom, and, if you’re a writer, what you’re building up next to you is text, right? So pretty soon you’ll be gone and the text will be left. But there’s a sense of is that experience or is that something else? Is that experience, like going for a walk, or eating, or all of these other things.

And again (to the brunt and shiv of us who cough up bloc-notes so regular-like):

. . . is the time that it takes to articulate your life—is that a good deal? Should you just not articulate it? You know, is it taking your life away from you?

. . . now I feel sometimes the space of writing is more interesting that doing anything else. It becomes kind of addictive, it feels more alive, and I think that that’s a little bit scary and threatening.

. . . I’m more interested in the way in which the kind of experience and consciousness of life that happens when you write can become more fascinating than the series of betweens and possibilities that are offered by non-writing.

It’s a terrific record of a conversation, wide-ranging, intelligent, consider’d, and points to how forcefully Moxley refuses the easy, and ideological pettiness, and the usual

idée reçue word on the street, the programmatic, the groupuscular, the ready slot. In it, she talks of deciding (mid-stride, some of the prose pieces done) “to do 43 poems. I set that number because I wanted to write as many as Rimbaud’s

Illuminations.” And:

One of the things I wanted to do in The Line was to go counter to all of my tendencies, you know—no artificial language, no complicated syntax, no traditional lyric, a tradition that I’ve explored and worked with in the past, and to use totally commonplace spoken English and very simple syntax.

Avoiding the line in order to resist the line’s tendency to fall into meter—“I needed to break that and go into what I considered a flat, prosaic, spoken tone.” (Oddly oppositional to a counter-attitude that says “aerate by lineating,” what one does to clotted prose.) Here’s a piece, about two thirds of the way through the series:

Run Through

Here’s to a rhythm that follows the ear. Or rather, here’s to you, heavy genealogy, you’ve been making me hungry for years. Mimesis was your meal ticket. The bounty went right through you when it should have become a door. A door to where? To some place beyond these endless deserts of shoddy salvation.

The legacy of your discomfort with loss and retention has made me the victim of my digestion. It’s all a matter of perspective, and I am, as the vehicle of these violent processes, completely ignorant of how they work. I must guess based on non-mechanical evidence and a total integration of the senses. They shall become one and none. Then the line inside my belly will show itself to my mind as it passes the boundary of my body’s calendar into an infinity of days. Though this hook-up may pain me, I suspect it necessary.

Certainly an echo of Rimbaud (lightly mocking the mocker) in “a total integration of the senses.” Too, in the deliberate tone, that weighing, testing tone that Rimbaud adopts (

“Reprenons l’étude au bruit de l’oeuvre dévorante qui se rassemble et remonte dans les masses.” “Back to our studies to the noise of the devouring work that gathers itself and rises up in the masses.”) against the (highly visible)

faux-lyrical outbursts (

“Fanfare atroce où je ne trébuche point!” “Terrible fanfare where I never stumble!”) that more regularly mark him. If the syntax is straightforward (it is), and the language is “flat, prosaic, spoken” (it’s not), what makes the piece one to return to—enamour’d—is precisely what makes

Illuminations a thing to marvel at, and pore over: shifting markers deliver’d with total commitment, total control and confidence. “Mimesis was your meal ticket.” It’s as if—rhythm points to how the ear commands the writing, something “old hat” about that—the burdens of the obvious, “heavy genealogy,” can’t one get beyond Olson—“making me hungry,” genealogy pointing to mimesis, the “next in line”—one way to eat, even if rather unsatisfyingly, “meal ticket.”

I’ll not dismantle further. A second attempt would result in—I suspect—several other (unmatch’d, though not discordant) pieces. “If copper finds itself a bugle, it’s not its fault . . .” is what Rimbaud follows that infamous “Je est un autre” with. Meaning, for all the care and deliberateness, what makes any song sing is incomprehensible, other, divine. Moxley: “vehicle of these violent processes, completely ignorant of how they work.”

Jennifer Moxley