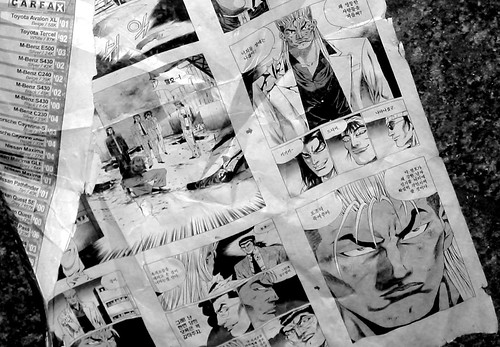

A Newspaper in the Street

Funny to come across little O’Hara homunculi whilst perusing Auden’s The Orators: An English Study (1932). Benefits of the epigone. (There’s no correlate between “hindsight” and “hind tit,” that latter’s reserved for litter-runts.) So, if Auden, in a categorizing spree, rambling along about “the excessive lovers of self,” identifies these as “they who even in childhood played in their corner, shrank when addressed,” do we immediately think of “Autobiographia Literaria”? (“When I was a child / I played by myself in a / corner of the schoolyard / all alone.”) Maybe.

What if we read “Are you just drifting or thinking of flight? You’d better not. No use saying ‘The mater wouldn’t like it,’ or ‘for my part I prefer to read Charles Lamb.’ Need I remind you that you are no longer living in Ancient Egypt? Time’s getting on and I must hurry or I shall miss my train”? Except for a few hoity Briticisms, isn’t that the fleet Frank?

Another. Auden, in a terrific ranging slippery catalogue of unity in diversity, with high scrutable side-commentary (the Zen-etch’d “Life is many; in the pine a beam, very still: in the salmon an arrow leaping the ladder” or the Stein-romping “An old one is beginning to be two new ones. Two new ones are beginning to be two old ones. Two old ones are beginning to be one new one. A new one is beginning to be an old one. Something that has been done, that something is done again by someone . . .”) writes:

One charms by thickness of wrist; one by variety of positions; one has a beautiful skin, one a fascinating smell. One has prominent eyes, is bold at accosting. One has waster sense; he can dive like a swallow without using his hands. One is obeyed by dogs; one can bring down snipe on the wing. One can do cartwheels before theatre queues; one can slip through a narrow ring. One with a violin can conjure up images of running water; one is skilful at improvising a fugue; the bowel tremors at the pedal-entry. One amuses by pursing his lips; or can imitate the neigh of a randy stallion. One casts metal in black sand; one wipes the eccentrics of a great engine with cotton waste. One jumps out of windows for profit. One makes leather instruments of torture for titled masochists; one makes ink for his son out of oak galls and rusty nails . . .Brilliant and grace-inflect’d and various. Is there a relationship one’d draw between that and O’Hara’s great burst of “sordid identifications” in “In Memory of My Feelings”?

GraceThirty or so years later, in the bowdlerized 1967 “First American Edition” of The Orators, Auden is dismissive of the work, saying—not discounting the coy rubric, nor the revisionist’s tendency to overkill—that the “name on the title-page seems a pseudonym for someone else, someone talented but near the border of sanity, who might well, in a year or two, become a Nazi.” Turning to “literary influences,” he says:

to be born and live as variously as possible. The conception

of the masque barely suggests the sordid identifications.

I am a Hittite in love with a horse. I don’t know what blood’s

in me I feel like an African prince I am a girl walking downstairs

in a red pleated dress with heels I am a champion taking a fall

I am a jockey with a sprained ass-hole I am the light mist

in which a face appears

and it is another face of blonde I am a baboon eating a banana

I am a dictator looking at his wife I am a doctor eating a child

and the child’s mother smiling I am a Chinaman climbing a mountain

I am a child smelling his father’s underwear I am an Indian

sleeping on a scalp

and my pony is stamping in the birches,

and I’ve just caught sight of the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria.

The sections entitled Argument and Statement [whereof I quoted] contain, as Eliot pointed out to me in a letter, ‘undigested lumps of St-John Perse.’ I had recently read his translation of Anabase. [My recollection of the sea-froth and gush of Anabase is apparently fictitious, or inaccurate.] The stimulus to writing Journal of an Airman came from two sources, Baudelaire’s Intimate Journals, which had just been translated by Christopher Isherwood, and a very dotty semi-autobiographical book by General Ludendorff, the title of which I have forgotten. [Is it just because I am in the midst of Nabokov’s The Gift that I find that detail suspect, Ludendorff too like any number of veal-flesh’d lumberers, strictly, “oafs,” in the Nabokov oeuvre?] And over the whole work looms the shaow of that dangerous figure, D. H. Lawrence the Ideologue, author of Fantasia of the Unconscious and those sinister novels Kangaroo and The Plumed Serpent. [Another lumberer, a prose-lumberer and bête-noire and I am sorry to see him mention’d.]Auden sees a “central theme” of “Hero-worship” in The Orators, “and we all know what that can lead to politically”—something that strikes me as more revisionist mumbo-jumbo and less noteworthy than the piece’s brash stylistic sources and how O’Hara succumb’d to it. (“From these stony acres, a witless generation, plant-like in beauty.”)

W. H. Auden, 1907-1973

(Photograph by Cecil Beaton)

(Photograph by Cecil Beaton)